Folks, Facts, & Fun From March 1931

News Headlines, Entertainment & Trivia from February, 1931: Ann Harding stars in the classic movie East Lynne; Cab Calloway records Minnie the Moocher; Pearl S. Buck’s Pulitzer Prize-winning best-seller The Good Earth is published

Classic Movie East Lynne is Released

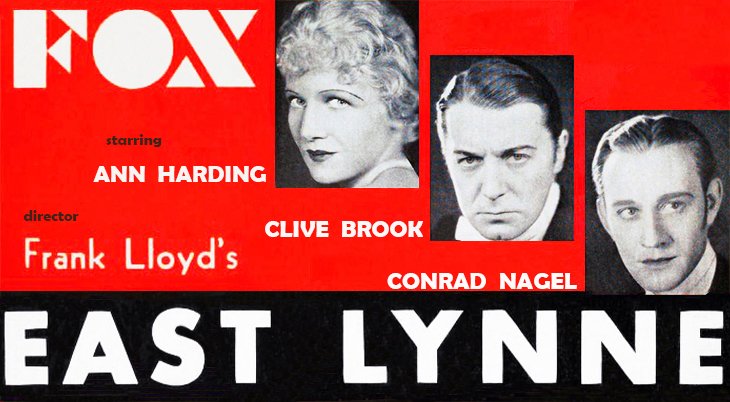

Director Frank Lloyd’s melodrama East Lynne starring Ann Harding, Conrad Nagel, and Clive Brook, was released in March 1931.

(East Lynne 1931 Movie Ad, Modified)

(East Lynne 1931 Movie Ad, Modified)

Screenwriters Bradley King and Tom Barry modified some plot points from the original best-selling 1861 novel by Mrs. Henry (Ellen) Wood, the setting was changed to 1875.

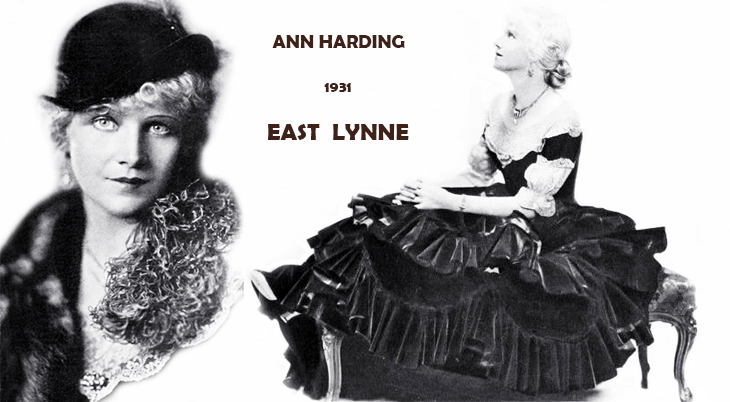

(Ann Harding 1931 East Lynne Photos: Autrey / Picture Play & The Filmgoer’s Annual 1932)

(Ann Harding 1931 East Lynne Photos: Autrey / Picture Play & The Filmgoer’s Annual 1932)

This 1931 film version of the popular story begins with the wedding of social butterfly Lady Isabel Dane (Ann Harding) to wealthy lawyer Robert Carlyle (Conrad Nagel). The couple takes up residence in Robert’s East Lynne mansion in England, which is run by Robert’s judgmental sister Cornelia (Cecelia Loftus). Isabel and Robert have a son, William (played by Ronnie Cosby as a child, and Wally Albright as a boy), and life becomes a bit routine and boring for Isabel.

Isabel and Robert meet her old beau beau, dashing world-traveler Captain William Levison (Clive Brook), and Robert invites him to stay with them.

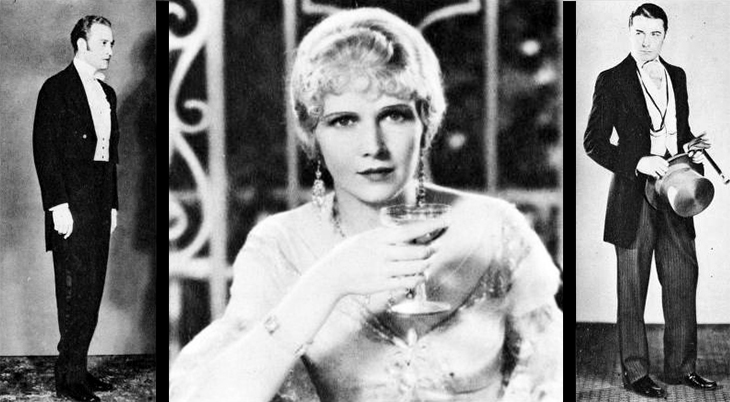

(Conrad Nagel, Ann Harding & Clive Brook 1931 East Lynne Photos: The Filmgoer’s Annual 1932)

When Robert is away, Isabel goes to a party without Cornelia, and the Captain flirts with her. Back at East Lynne after the party, the Captain kisses her, and Isabel runs off (alone) to her bedroom.

(Clive Brook & Ann Harding 1931 East Lynne Photo: The Filmgoer’s Annual 1932)

(Clive Brook & Ann Harding 1931 East Lynne Photo: The Filmgoer’s Annual 1932)

The Captain leaves early the next morning, and when Robert returns, Cornelia tells him a far worse version of the story. Robert won’t let Isabel explain, and they argue.

(Conrad Nagel & Ann Harding 1931 East Lynne Photo: The Filmgoer’s Annual 1932)

(Conrad Nagel & Ann Harding 1931 East Lynne Photo: The Filmgoer’s Annual 1932)

Isabel leaves by herself when Robert won’t let her take William with her. Two months later, a court case has taken place and Isabel departs England, setting sail from Dover.

(Ann Harding 1931 East Lynne Photo: The Filmgoer’s Annual 1932)

(Ann Harding 1931 East Lynne Photo: The Filmgoer’s Annual 1932)

Who should be aboard ship but Captain Levison, now an Ambassador in Vienna. They attend a ball in Vienna together. The next day Levison is fired as Ambassador for his wrong-doings, and exiled from England. Isabel goes with him to Paris, where Levison soon shows his ugly side. Isabel’s father Lord Mount Severn (O.P. Heggie) visits her in Paris, to tell her that her divorce is now final and she is not allowed to see her son because of the scandal surrounding her.

Paris is at war and under fire as Isabel races through the streets, determined to return to England and see her son again one last time. She’s hurt when part of a building falls on her, and is told she will soon be blind. She returns to England anyway and sneaks in to see her son, thanks to her loyal friend, William‘s nanny Joyce (Beryl Mercer). Isabel stays all night in her son’s room and the next morning when she wakes up, she’s blind. Isabel walks out of the house and falls over a cliff onto the rocks to her death.

Reviewers uniformly praised Ann Harding’s acting (she IS the picture) and set design by Joseph Urban. Harrison’s Reports summed up the film’s risque (for 1931) storyline for movie-goers: “Not good for Sundays in small towns.”

East Lynne was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Production (Best Movie), along with The Front Page, Skippy, and Trader Horn, but Cimarron walked way with the Oscar.

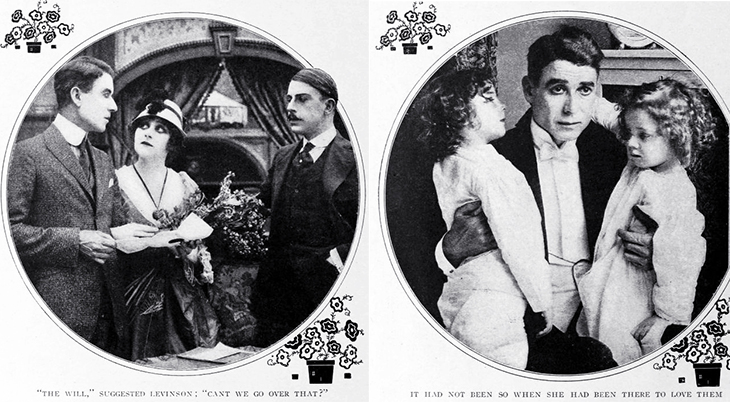

This was the third re-make of East Lynne by Fox Films. The previous Fox versions were two silent movies – the first, a 1916 film directed by Bertram Bracken and starring Theda Bara, below.

(Ben Deely, Theda Bara & Stuart Holmes 1916 East Lynne Photos: Fox / Motion Picture Magazine)

(Ben Deely, Theda Bara & Stuart Holmes 1916 East Lynne Photos: Fox / Motion Picture Magazine)

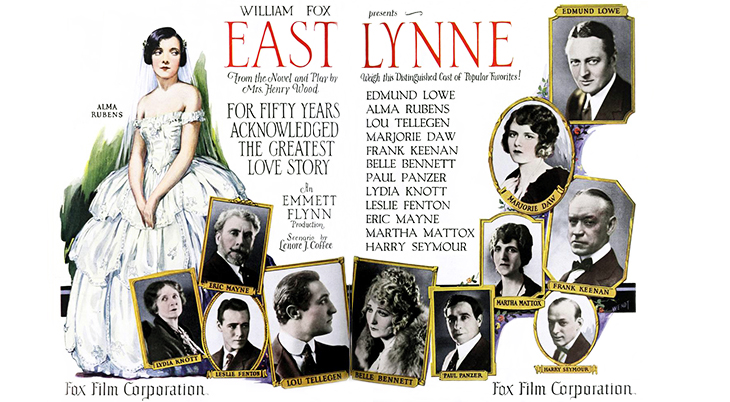

The second in 1925 movie had an all-star cast, with Alma Ruben, Edmund Lowe, Lou Tellegen, Marjorie Daw, Frank Keenan, Leslie Fenton, Paul Panzer, and Belle Bennett.

(East Lynne 1925 Movie Ad: Fox Film Corporation)

(East Lynne 1925 Movie Ad: Fox Film Corporation)

In fact, this popular Victorian-era novel has been adapted countless times for the stage, radio, TV, and films. In addition to the 3 Fox versions, it’s been re-made (or parodied as a comedy) movie at least 15 other times, beginning with the first short film version in 1902.

(Alma Rubens in East Lynne 1925 Ad: Fox Film Corporation)

(Alma Rubens in East Lynne 1925 Ad: Fox Film Corporation)

A few of the more notable movie versions::

- East Lynne; or, Led Astray (1908), a Vitagraph short directed by J. Stuart Blackton.

- East Lynne (1912), a Thanhouser Films version with scenario & direction by Theodore Marston. Starring Marguerite Snow, James Cruze, William Russell, and Florence La Badie.

(James Cruze, Florence La Badie & Marguerite Snow 1912 East Lynne: Thanhouser / The Moving Picture World)

(James Cruze, Florence La Badie & Marguerite Snow 1912 East Lynne: Thanhouser / The Moving Picture World)

- East Lynne in Bugville (1914), a comedy short play-within-a-play starring Pearl White, about a production of East Lynne that goes awry. Directed by Phillips Smalley.

- East Lynne (1915), a Biograph studios short film starring Louise Vale, Franklin Ritchie, Alan Hale and his wife Gretchen Hartman.

- East Lynne with Variations (1919), a parody comedy short from Mack Sennett Studios starring Ben Turpin, Marie Prevost, and Heinie Conklin, with Tom Kennedy and Alice Lake.

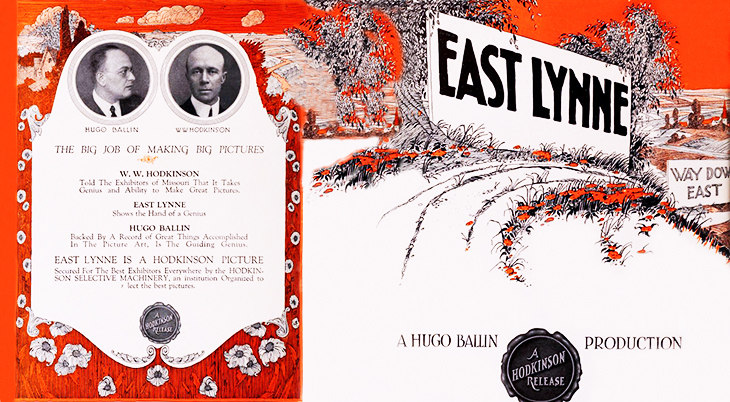

- East Lynne (1921), by the Hugo Ballin film studio, with direction and adapted scenario by Hugo Ballin. Starring Mabel Ballin and Edward Earle.

(East Lynne 1921 Movie: Hodkinson / Motion Picture News)

(East Lynne 1921 Movie: Hodkinson / Motion Picture News)

- Ex-Flame (1930), a re-titled version with the same storyline, and set in 1930s England. Directed by Victor Halperin and starring Neil Hamilton, Marion Nixon, Norman Kerry, Joan Standing (Dracula), Snub Pollard, and Louis Armstrong as himself.

- East Lynne (1964), a made-for-TV movie starring Michael Denison, Dulcie Gray, Peter Graves, and Marion Grimaldi.

- East Lynne (1982), a 1982 TV film starring Lisa Eichhorn, Martin Shaw, and Tim Woodward, with Annette Crosbie, Jane Asher, and Gemma Craven.

Cab Calloway Records Minnie The Moocher

The comedy jazz song Minnie The Moocher written by Cab Calloway, Irving Mills, and Clarence Gaskill, was first recorded on March 3, 1931 by Cab Calloway and his Cotton Club Orchestra.

Minnie The Moocher sold over a million records, was the biggest hit single of 1931, became an enduring signature tune for Cab Calloway. It was entered in the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1999.

Calloway’s song inspired the 1932 animated Betty Boop movie Minnie The Moocher, and can also be heard in other Betty Boop animated films (The Old Man of the Mountain, 1933; Making Stars, 1935; and Betty Boop for President, 1980). Below, the 1932 cartoon.

Minnie the Moocher can be heard on many TV episodes and in films, including these notable movies:

- The Big Broadcast (1932), a musical romantic comedy starring Bing Crosby, Stuart Erwin, Leila Hyams, George Burns, Gracie Allen, Kate Smith, and other performers of the day.

- When You’re in Love (1937), a musical romantic comedy starring Cary Grant, Grace Moore, Aline MacMahon, and Thomas Mitchell.

- Manhattan Merry-Go-Round (1937), a musical comedy starring Ann Dvorak, Leo Carillo, James Gleason and Phil Regan, with Joe DiMaggio thrown in for good measure as himself.

- The Blues Brothers (1980), a musical adventure-comedy starring John Belushi & Dan Aykroyd.

- The Cotton Club (1984), a drama set in Harlem of 1928-1930s, starring Richard Gere, Gregory Hines, Diane Lane, Lonette McKee, Laurence Fishburne, Bob Hoskins, Nicholas Cage, James Remar, Fred Gwynne, and Gwen Verdon.

- Look Who’s Talking Too (1990), a romantic comedy starring John Travolta, Kirstie Alley, Olympia Dukakis, Bruce Willis, and Elias Koteas.

- My Music: The Big Band Years (2009), a documentary retrospective of 1930s-1950s music hosted by Peter Marshall.

- Magic Magic (2013), a thriller starring Michael Cera.

- Mr. Jones (2019), a thriller set in the 1930s starring James Norton and Peter Sarsgaard.

Pearl S. Buck Publishes The Good Earth

American author Pearl S. Buck’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel of China, The Good Earth was first published on March 2, 1931. In the Top Ten Best-Seller lists for the next five months, The Good Earth was the #2 best-selling book of 1931 (after Shadows on the Rock, by Willa Cather). Although the film rights to the novel were bought by MGM in 1931, some in the film industry were skeptical that the movie would ever be made, according to Motion Picture Herald (1932):

“It involves Oriental characters exclusively and its drawing power, in consequence, is regarded with some misgivings by the producer.”

The Good Earth was made into a film, but it took three years and a lot of money (the studio recorded a net loss of almost $1 million) before it made it to the screen. The wait was worth it – the 1937 movie The Good Earth starring Luise Rainer and Paul Muni, was nominated for five Academy Awards, and won three.

(Pearl S. Buck c. 1932 Photo: Arnold Genthe / US LoC)

(Pearl S. Buck c. 1932 Photo: Arnold Genthe / US LoC)

Born on June 26, 1892 in West Virginia, author Pearl S. Buck (nee Sydenstricker) lived in China with her missionary parents from the age of 5 months. She returned to America in 1911 in order to attend college, but returned to China after graduating in 1914.

In 1917 she married missionary John Lossing Buck and the couple became university teachers in Nanjing, China. Three years after the birth of their severely mentally disabled daughter Carol in 1921, they made the trip back to the United States.

While in the U.S. for a year, they adopted daughter Janice Comfort Buck, and Pearl earned a master’s degree from Cornell University.

The Buck’s returned to China in the fall of 1925 and were rescued by American gunboats after violence broke out in Nanjing in 1927. Pearl Buck began writing and returned to America in 1929 by herself in order to find long-term care for Carol and a publisher for her first novel, East Wind: West Wind. She was successful on both counts. John Day publishing house founder and editor Richard J. Walsh published the book, beginning a partnership which would be fruitful and life-changing for both. Buck returned to Nanjing and began writing what would become her next novel, The Good Earth.

Pearl Buck travelled to the U.S. in 1934 again with Janet, while John Buck stayed behind. By the end of 1935, Pearl had published her fourth book, A House Divided, divorced John Buck, and married her publisher Richard J. Walsh (who had also obtained a divorce from his wife). The family lived at Green Hills Farm in Bucks County, PA, and according to her Penn Arts & Sciences biography, they adopted another six children.

Over the next 25 years, Pearl S. Buck wrote another 37 novels, and many more short stories, children’s books, and non-fiction works, under her own name and the pseudonym John Sedges. Almost all of her books were published by John Day publishing house. She was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for The Good Earth in 1938.

In addition to The Good Earth, another 9 of her works were adapted for the screen, notably

- Dragon Seed – a 1942 novel made into a 1944 feature film starring Katharine Hepburn, Walter Huston, Aline MacMahon, Akim Tamiroff, Turhan Bey, Hurd Hatfield, and Agnes Moorehead.

- China Sky – a 1941 novel which became the 1945 movie of the same name starring Randolph Scott, Ruth Warrick, Ellen Drew, Anthony Quinn, Benson Fong, and Philip Ahn.

- The Big Wave – a 1940 children’s book about a tsunami, made into a 1961 movie starring Sessue Hayakawa.

- Pavilion of Women – a 1946 novel made into a 2001 movie starring Willem Dafoe and John Cho.

- Satan Never Sleeps (1962), made into a film the same year it was published. Stars William Holden, Clifton Webb, and France Nuyen.

As a philanthropist, among her charitable works were Welcome House, the first international, interracial adoption agency, which she co-founded in 1949 with fellow novelist James A. Michener and the Oscar Hammerstein II’s; the Pearl S. Buck Foundation to address poverty in Asian countries; and an orphanage in South Korea. Although she tried to return to China many times, Pearl was always blocked by the Chinese government.

Several years after her husband Richard J. Walsh died in 1960, Buck began co-authoring books with Theodore Harris. She entrusted the management of her finances (personal and foundations) to him as well, and he managed her daily affairs. Despite charges that Harris was diverting funds for his personal use, Buck left him a significant bequest in her will, which was challenged and overturned by her surviving children. Pearl S. Buck died of lung cancer at the age of 80 on March 6, 1973. Her daughter Janet Comfort Walsh’s 2016 The Guardian obituary states that Janet was survived by 4 of her adopted siblings, and her stepbrother Paul Buck.

*Images are believed to be in the public domain or Creative Commons licensed & sourced via Wikimedia Commons, Vimeo, YouTube, or Flickr, unless otherwise noted*