Done in March 1951

Baby Boomer Trivia From March 1951: Trial of American spies Julius & Ethel Rosenberg; Korean War Operation Ripper to recapture Seoul; and The King and I Broadway debut starring Gertrude Lawrence and Yul Brynner.

Trial of Spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg

Seniors and older baby boomers may remember the trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, Jewish American spies for the Soviet Union during World War II, which began on March 6, 1951.

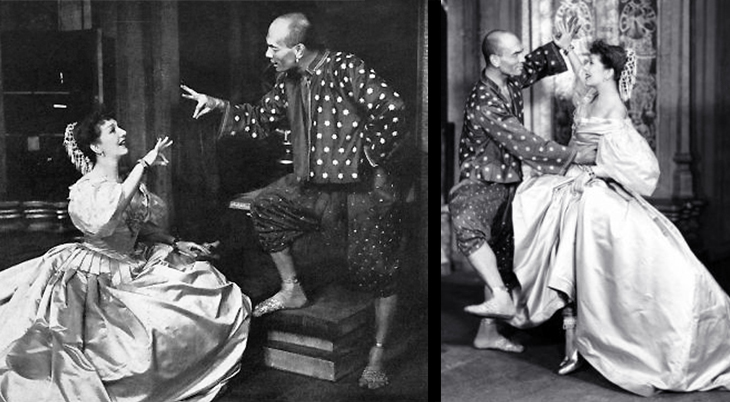

(Ethel & Julius Rosenberg 1951 | David Greenglass c 1950)

(Ethel & Julius Rosenberg 1951 | David Greenglass c 1950)

While attending City College of New York on his way to an electrical engineering degree in the 1930’s, Julius Rosenberg had become a leader in the Young Communist League USA. He met Ethel Greenglass, another member of the Young Communist League, in 1936 and they married in 1939.

Julius Rosenberg joined the U.S. Army Signal Corps in 1940 after World War II had broken out in Europe, and was recruited by the Soviet Union NKVD as a spy in 1942. Julius began providing classified documents to the Soviets and recruiting other spies.

Ethel’s younger brother David Greenglass had joined the Young Communist League in 1943, and after keeping his communist associations secret, was assigned to the top secret Manhattan Project (developing the first atomic weapons), from July 1944 – August 1946.

Espionage activities during and after WWII were uncovered in 1950, with the result that David Greenglass was arrested; he quickly implicated his brother-in law-Julius Rosenberg. Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were then charged with conspiracy to commit espionage, and passing information to the Soviet Union.

By 1950, the Cold War was heating up, HUAC (House Un-American Committee) Hearings were ongoing, the Hollywood Ten had been blacklisted, and McCarthyism had whipped up political and public sentiment against any perception of alignment with communist sentiments.

During grand jury indictment testimony in the summer of 1950, David Greenglass testified that Ethel Rosenberg was not involved in espionage, and said he only gave documents to Julius when they met alone on a street corner.

David’s wife Ruth Greenglass contradicted this when she testified that Julius Rosenberg had recruited Ethel, and gotten Ethel to recruit David.

Ruth said that Ethel had urged her (Ruth), to encourage David to provide information to Julius.

In February 1951, just before the Rosenberg’s trial began, David Greenglass recanted his grand jury testimony and said he had brought his notes to Julius and Ethel’s apartment, and Ethel had typed the notes up for Julius.

When re-interviewed at that time, Ruth now also added this detail – that Ethel had typed up the notes.

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg refused to give any testimony at their trial and were convicted on March 29, 1951.

They were sentenced to death on April 5, 1951 and executed by electric chair on June 19, 1953.

Charges against Ruth Greenglass were dropped. David Greenglass was convicted of his espionage charges and was imprisoned for 9 years, until 1960.

After Ethel and Julius Rosenberg’s executions, their young sons Michael (b. 1943) and Robert (b.1947) were abandoned by frightened relatives. Eventually they were adopted from an orphanage by teacher and social activist Abel Meeropol; they took his last name.

In a 1996 New York Times interview, David Greenglass said that he had lied about how involved his sister Ethel Rosenberg was, in order to protect his wife Ruth. He said he “didn’t remember” who typed up the notes, but implied that Ruth had typed them to give to Julius.

Ruth Greenglass died in 2008. That same year, David Greenglass objected to his grand jury testimony from over 5 decades earlier being made public, and a Judge ruled in his favor. David Greenglass was living under an assumed name in a New York City nursing home when he died in 2014 at the age of 92. His grand jury testimony was finally released to the public in 2015.

Robert Meeropol and his brother Michael fought for many years to clear their mother’s name. 70+ year old retired attorney Robert Meeropol spoke to the Jewish Learning Institute in 2020 about his parents case, their execution, and the death penalty.

Ethel Rosenberg’s name has never been cleared of the charge of spying.

Korean War Operation Ripper Recaptures Seoul

By March 1951, the Korean War had been underway for a little over 8 months. On March 7, 1951, the Operation Ripper attack by the Eighth Army commenced, under the direction of U.S. General MacArthur, the Supreme Commander in Korea.

By March 12 1951, the city of Seoul, Korea had been recaptured by United States/United Nations forces, and Operation Ripper was completed. A month later, General MacArthur was relieved of his command by U.S. President Truman for a variety of reasons, including threatening to destroy China unless it surrendered.

Broadway Musical The King and I Opens

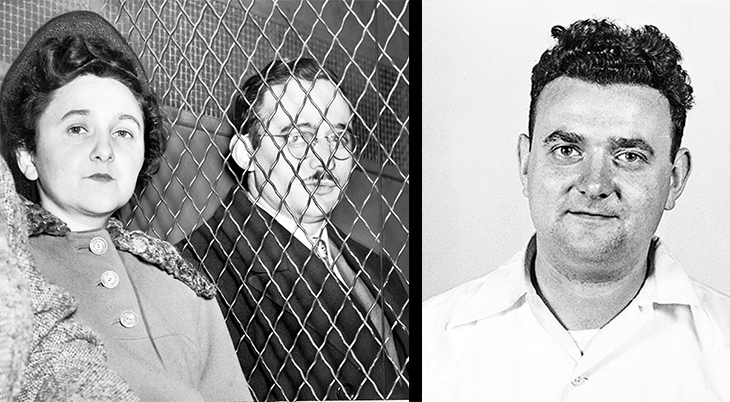

The Broadway musical The King and I starring Gertrude Lawrence and Yul Brynner, opened on March 29, 1951 at the St. James Theater in New York City.

(Gertrude Lawrence & Yul Brynner 1951 The King and I)

(Gertrude Lawrence & Yul Brynner 1951 The King and I)

Based on Margaret Landon’s 1944 novel Anna and the King of Siam, the novel was first adapted for the screen in the 1946 movie Anna and the King of Siam, starring Irene Dunne, Rex Harrison, and Linda Darnell.

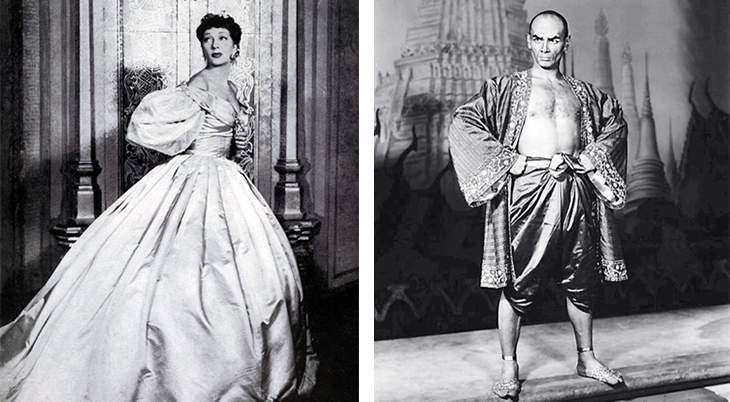

Theatrical lawyer Fanny Holtzmann contacted Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II in 1950 about creating a Broadway musical adaptation to star her client, British actress Gertrude Lawrence.

(Gertrude Lawrence 1929 Photo: Radio Digest)

(Gertrude Lawrence 1929 Photo: Radio Digest)

Lawrence had first made a name for herself as an English singing and comedy star of 1920s radio and stage in England.

She’d acquired the stage adaptation rights for The King and I from Landon, hoping to arrest the downward slide of her career that had begun in the latter half of the 1940s.

Rodgers and Hammerstein wrote the “book” and score for the musical, and Jerome Robbins contributed the choreography.

When English actor Rex Harrison was unavailable to reprise his film role for the stage, Russian-American Yul Brynner was given the role of the King.

Despite the increasingly evident illness of star Gertrude Lawrence, the Broadway debut performance at the St. James Theatre was a hit, and musical history was made.

The following March, the 1952 Tony Awards were held in the Waldorf-Astoria Grand Ballroom, with Helen Hayes as presenter. Both Gertrude Lawrence and Yul Brynner won Tony Awards for their performances, and the show won the 1952 Tony Award for Best Musical. The other 2 Tony Awards that went to The King And I were for Scenic Designer Joe Mielziner, and Costume Designer Irene Sharaff.

Gertrude Lawrence’s health continued to deteriorate and she was hospitalized with pleurisy, then had bronchitis a few months later. She was replaced by Celeste Holm for 6 weeks in the summer of 1952 so she could rest. In September 1952 Gertrude Lawrence died unexpectedly of liver and abdominal cancer; the lights were dimmed on Broadway in her honour.

Lawrence’s understudy Constance Carpenter stepped in to play Anna for the remaining Broadway shows. The King and I enjoyed a run of 1,246 performances on Broadway, followed by a U.S. national tour starring Patricia Morison and Yul Brynner. A long-running production in London, England starred Valerie Hobson and Herbert Lom.

Yul Brynner also starred in the 1956 movie Anna and the King opposite Deborah Kerr, and was in several revivals of The King and I. Just before his death from lung cancer in 1985, Brynner completed another 4-year run in The King and I on Broadway. All told, Yul Brynner was in 4,625 performances of The King and I on stage.

Note: This article was first published in 2016. It has been updated with new / additional content.

*Images are believed to be in the public domain or Creative Commons licensed & sourced via Wikimedia Commons or Flickr, unless otherwise noted*