The Regency's Two Georges

The two men that shaped the very nature of the Regency era (portrayed splendidly, if not 100% accurately in the popular Bridgerton television series), were George “Beau” Brummell, and George, Prince of Wales (aka The Prince Regent, “Prinny“; later King George IV).

(George “Beau” Brummell c. 1790s-1800s: Joshua Reynolds | George, Prince of Wales / Prince Regent 1816: Henry Bone)

(George “Beau” Brummell c. 1790s-1800s: Joshua Reynolds | George, Prince of Wales / Prince Regent 1816: Henry Bone)

The Prince Regent – George, Prince of Wales

If there had been no George, Prince of Wales, who was declared Prince Regent during his father King George III’s extended mental illness, there would have been no Regency Era of history, as it is referred to today.

(Prince of Wales, George IV c. 1798 Portrait: Sir William Beechey R.A./ John Hammond / Royal Academy of Arts)

The oldest child of King George III and Queen Charlotte’s 15 children, due to his father King George III’s mental illness, Prince George (Prince of Wales) served as the Prince Regent beginning in 1811. The Prince Regent’s charm, extravagant lifestyle and dress, irresponsibility, selfishness, and a tendency to corpulence, were among his most distinguishing features.

(King George III c 1765: Allan Ramsay| Queen Charlotte 1781: Thomas Gainsborough)

(King George III c 1765: Allan Ramsay| Queen Charlotte 1781: Thomas Gainsborough)

Born August 12, 1762, at the age of 21 (in 1783) Prince George established his primary residence at Carlton House, a Westminster mansion on the south side of Pall Mall, near St. James Park.

“”Hampton court palace and Carleton house are the places destined for the summer and winter residence of his royal highness the prince of Wales…Carlton house is said to want such a variety of repairs as will take up six months; so that his royal highness will not remove thither till next year.” – Wednesday’s Post, London, June 24 From the London Gazette – The Chelmsford Chronicle, June 27, 1783

Prince George’s reputation for extravagance in all things was well deserved, with mounting debt and scandals accumulating year over year. The phrase “Carlton House set” often used in novels set in the Regency era, refers to his entourage of hangers-on.

(Maria Fitzherbert 1784 Portrait: Thomas Gainsborough)

(Maria Fitzherbert 1784 Portrait: Thomas Gainsborough)

Prince George secretly married his mistress, the twice-widowed Maria Fitzherbert, in a invalid marriage ceremony in 1785.

In the summer of 1788, his father King George III’s mental health collapsed and the British parliament prepared a Regency Bill to have Prince George act in his stead. George III recovered before the bill was passed, but a foundation had been laid in the event of a future relapse.

His affair with Maria Fitzherbert was such public knowledge by 1792 that she was featured in a magazine about Carleton House:

“The Carlton House Magazine; or, Annals of Taste, fashion, and politeness. Calculated to form the Man of Honour, the intelligent Companion, and the accomplished Gentleman. To be continued Monthly, embellished with superb engravings. The Embellishments of the Numbers already published are as follows: Those which decorate No. I are, an elegant Frontispiece; a Portrait of the Prince of Wales; and a View of Carlton House. No. II is illustrated with an exact Representation of the Duchess of York’s Show, with its true dimensions; a Tea-table Conversation Piece in high life; and a perspective View of the Inside of the King’s Theatre. No. III is enriched with an accurate Likeness of Mrs. Fitzherbert, and a perspective View of York House. No. IV has an elegant Monument to the memory of Sir Joshua Reynolds; and whimsical Caricature…” – The Bath Chronicle, April 26, 1792

Having accumulated a mountain of debt that his father King George III refused to pay, the Prince of Wales agreed to marry his cousin, Princess Caroline of Brunswick-Wolfenbuttel, in April 1795.

Prince George and Princess Caroline hated each other cordially. They separated after their only child, daughter Princess Charlotte, was born in 1796.

(Princess Caroline of Brunswick 1804: Thomas Lawrence | Princess Charlotte c. 1817: George Dawe)

(Princess Caroline of Brunswick 1804: Thomas Lawrence | Princess Charlotte c. 1817: George Dawe)

Meanwhile, Prince George continued to visit his mistress Maria Fitzherbert on and off. He also had other mistresses, some of whom were rumored to have given birth to his children.

His wife Princess Caroline was also indiscreet in her affairs, and the couple battled over custody of their daughter Princess Charlotte (George won). Public knowledge of the Prince and Princess affairs was not confined to England.

“The affair of the Princess of Wales, appears to us as an act of providential retributive justice, for although it is very probable the unfortunate woman is guiltless of infidelity to the Prince of Wales, she certainly was well aware, that the Prince had a wife already living, who is called indeed Mrs. Fitzherbert, and who, if they do not consider religion as a farce (which unhappily is the practice of too many who profess religion,) it must be acknowledged, that before the Almighty presence, the lady called Mrs. Fitzherbert is the wife of that Prince; indeed it is notorious, that he maintains intercourse with his first wife still; and very probably the complaints of infidelity, are no more than preludes to a divorce from the German Princess, and very possibly, the passage of some law, by which Mrs. Fitzherbert may become queen – for the days of George the III, cannot now be long in the land, and as the king can do no wrong in England, he may return to his first love; and the German Princess may, like Catherine of Arrogan or Anne of Cleves, go to a nunnery – or to Mecklenburg.” – By the Mails – Incidents Abroad, Vermont Gazette, September 8, 1806

Their daughter Princess Charlotte died in 1817 at the age of 21.

(Prince of Wales, George IV 1816 Portrait: Thomas Lawrence / Vatican Museums)

(Prince of Wales, George IV 1816 Portrait: Thomas Lawrence / Vatican Museums)

King George III suffered another mental breakdown in 1810, and from 1811 until his father died in January 1820, Prince George served as Prince Regent. He then reigned as King George IV of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and King of Hanover, until his own death in June 1830.

Hence this era of history, the years 1811 to 1820; and from approximately the 1780s through the 1820s before and after that – are referred to as the Regency Era. The Georgian age of British history which encompasses the Regency era, began in 1714 when King George I became King of England, and ended in 1837 when George IV’s successor – his younger brother King William IV died. The Victorian era began when King William IV’s niece was crowned Queen Victoria.

George “Beau” Brummell

Typical ladies Regency fashions were a unique style with a high waist and slim skirt – quite different from the decades and centuries before and after the Regency era, when ladies dresses had snugly fitted waists and wide skirts.

At the beginning of the Regency era, men’s fashions were as extravagant and colourful as the women’s, in some cases, more so. Many young men in England adopted fashion extremes (neckcloths so high they could barely turn their heads; garish clothing, etc.), in an attempt to join the “dandy set”; they were often scorned by others.

Not so Beau Brummell…the most famous fashion arbiter of Regency England. George Bryan “Beau” Brummell, was born on June 7, 1778, younger son to William Brummell and his wife Jane (nee Richardson). William Brummell enjoyed the patronage of Lord North (2nd prime Minister of Great Britain, 1770-1782), and was given various appointments which helped him to accumulate a middling amount of wealth.

(William and George Brummell 1781 Portrait: Joshua Reynolds / Kenwood House) wiki pd

(William and George Brummell 1781 Portrait: Joshua Reynolds / Kenwood House) wiki pd

George “Beau Brummell”, his older brother William, and his sister Jane, all grew up on the 550-acre Donnington Grove Estate near Newbury, in a house built by former owner James Pettit Andrews c. 1763-1772.

(Donnington Grove Estate: Donnington Grove Hotel in Newbury)

(Donnington Grove Estate: Donnington Grove Hotel in Newbury)

“After Lord North’s resignation, Mr. Brummell retired to the country, and in the year 1788 served the office of high sheriff for Berkshire. In the immediate vicinity of his seat, the Grove, near Donnington Castle…Donnington Grove was universally acknowledged to be one of the most agreeable houses in the neighborhood….The society which Mr. Brummell received at Donnington was of the best and most talented description; both Fox and Sheridan visited there.” – Beaux & Belles of England: Beau Brummell (1844), by William Jesse

Both Charles James Fox and Richard Brinsley Butler Sheridan were prominent Whig politicians and friends of William Brummell Sr. Richard Sheridan had been a playwright and theatre owner in the 1770s, who eventually became Treasurer of the Navy from 1806-1807.

(Beau Brummell Statue on Jermyn Street, London 2009 Photo: DonJay)

(Beau Brummell Statue on Jermyn Street, London 2009 Photo: DonJay)

George Byron Brummell began setting fashions for upper class students and young noblemen while he was at Eton, and then Oxford University (age 15).

Brummell was known for his quick wit, love of playing tricks, and wearing understated and perfectly fitted clothing – from boots, neckcloths, and coats, to full-length trousers, which signaled the gradual end of wearing knee-length breeches for evening wear. His attention to personal hygiene and grooming – from daily bathing, shaving, and brushing his teeth – changed the grooming habits of the upper classes, who followed his example.

The three Brummell offspring were orphaned when their mother Jane died in 1793, and their father William Brummell Sr. in 1794. The estate was sold and the proceeds divided amongst the 3 children.

In 1794, a 16-year-old George Byron Brummell left Oxford after only a year, to join the Tenth Royal Hussars – the personal regiment of George, Prince of Wales. Prince George was a great admirer of Brummell; his patronage was a huge asset to Brummell from the start, as evinced when a still teenage Brummell was made a captain in 1796.

When his regiment was sent to Manchester in 1797, Brummell resigned his commission in order to stay in London. He wanted easier access to the culture and society of which he was now the acknowledged fashion leader.

The 1954 film Beau Brummell starring Stewart Granger as the style icon of the 1790s-1820s, features some very authentic-looking womens fashions. Particular attention was paid to the men’s hairstyles and Regency period costumes.

(Stewart Granger models different neckcloths in Beau Brummell, 1954).

(Stewart Granger models different neckcloths in Beau Brummell, 1954).

Brummell’s devotion to bread and cheese was well known, as was his aversion to vigorous exercise. His first biographer, Captain William Jesse, interviewed Brummell’s friends during his life in England and in France, and was given letters written or received by Brummell before he left England..

“Certain it is that he hated personal exertion in any way, and it was difficult to make him give up his book and shoulder his gun, to join in a scramble over hedgerows and ditches…Though Brummell was so much at Belvoir, and kept a stud of horses there, he was never a ‘Melton man;’ and his friends, as well as every one else, were amazingly astonished when he joined in the pleasure of the chase; for, like many other gentlemen, he did not like it: it did not suit his habits, and his servant could never get him up in time to join the hounds, if it was a distant meet: but even if the meet was near, and they found quickly, he only rode a few fields, and then shaped his course in an opposite direction, or paid a visit to the nearest farm-house, to satisfy his enormous appettite for bread and cheese. I have heard him, but many years after, laugh amazingly over these incidents of his Melton days, and say in his usual droll way, that he ‘could not bear to have his tops and leathers splashed by the greasy galloping farmers.” – The Life of George Brummell, Esq., Commonly called Beau Brummell (1844), by Captain William Jesse

An 1828 essay about George Brummell entitled Brummelliana, denoted society’s fascination with the fashions and foibles of Beau Brummel.

Of all the beaux that ever flourished – at least, of all that ever flourished to the same score – exemplary of waistcoat, and having authoritative boots from which there was no appeal – he appears to have been the only one who made a proper and perfect union of the coxcombical and ingenious. Others may may have been as scientific on the subject of bibs, in a draper-like point of view; and others have said as good things…Beau Fielding, we believe, stands on record as the handsomest of beaux. There is a beau Skeffington, now rather Sir Lumley, who, under all his double-breasted coats and waistcoats, never had any other than a single-hearted soul; he is to be recorded as the most amiable of beaux; but Beau Brummell for your more than finished coxcomb. He could be grave enough, but he was anything but a solemn coxcomb. He played with his own spectre. It was found a grand thing to be able to be a consummate fop, and yet have the credit of being something greater; and he was both. Never was anything more exquisitely conscious, yet indifferent; extravagant, yet judicious.:”

“Upon receiving some affront from an illustrious personage, he said that was rather too good. By gad, I have half a mind to cut the young one [Prince George], and bring old G_____e ] King George III] into fashion.”*

“He told a friend that he was reforming his way of life, ‘For instance’ said he, ‘I sup early; I take a little lobster, an apricot puff, or so, and some burnt champagne, about twelve; and my man gets me to bed by three.” – Brummelliana, Literary Cadet and Rhode-Island Statesman, March 8, 1828.

Friends of Beau Brummell

Brummell counted among his friends not only George, Prince of Wales, but other leaders of London society. The “mad, bad, and dangerous to know” poet Lord Byron was a particular friend of Brummell’s, although Byron was not liked by the Prince Regent.

William Arden, 2nd Baron Alvanley & The Dandy Club

Brummell’s closest friends were Henry Mildmay, Henry Pierrepoint, and William Arden, 2nd Baron Alvanley. Together these four friends formed “The Dandy Club” set at Watier’s, an exclusive gentleman’s gaming club founded in 1807 Regency London.

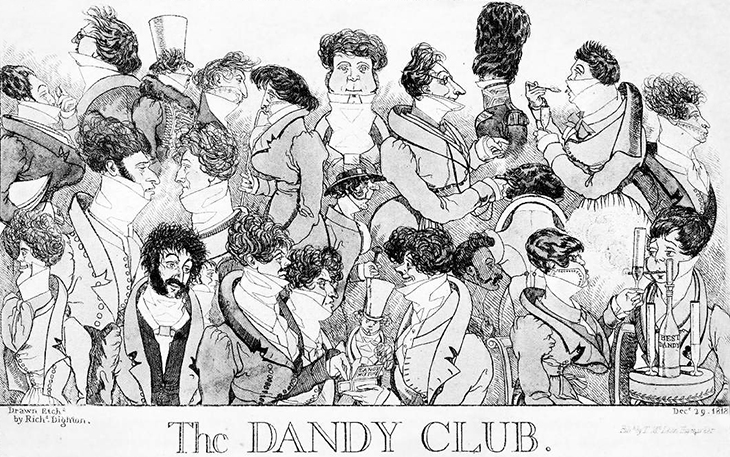

(The Dandy Club 1818 Caricature: Richard Dighton the younger)

(The Dandy Club 1818 Caricature: Richard Dighton the younger)

Prince George’s chef Jean-Baptiste Watier was the chef for the club, which was short-lived; Watier’s closed in 1819.

(William Arden, 2nd Baron Alvanley c. 1820s-1840s: Edwin Landseer)

(William Arden, 2nd Baron Alvanley c. 1820s-1840s: Edwin Landseer)

Lord Alvanley had the reputation of being the wittiest man in England, and was well-liked by the Prince Regent. Alvanley eventually had to sell his family estates in order pay off the debts he accumulated over decades. Lord Alvanley died in November 1849; having never married and with no known children, his brother inherited his title.

Frederick & Frederica, Duke and Duchess of York

Frederica, Duchess of York (nee Princess Frederica Charlotte of Prussia in 1767), married the Prince of Wales’ younger brother, Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany, in 1791.

(Frederica Duchess of York c. 1790s-1800s: John Hoppner | Frederick, Duke of York and Albany 1816: Thomas Lawrence)

(Frederica Duchess of York c. 1790s-1800s: John Hoppner | Frederick, Duke of York and Albany 1816: Thomas Lawrence)

Brummell was great friends with both the Duke and the Duchess of York, despite that royal couple’s separation in the mid 1790s.

The Duchess of York lived the remainder of her life at Oatlands Park in Surrey, where she kept cats, dogs, and monkeys. The Duchess of York was known for her kind, gentle, and in the case of Beau Brummell, most generous nature. Frederica died in August 1820 at the age of 53.

Prince Frederick served as Commander-in-Chief of the British military during different wars with French forces lead by Napoleon during the French Revolution. Having retired from the army he When Prince George’s daughter Charlotte died in 1817, Frederick was next in line to the throne behind Prince George. He passed away in January 1827, age 63.

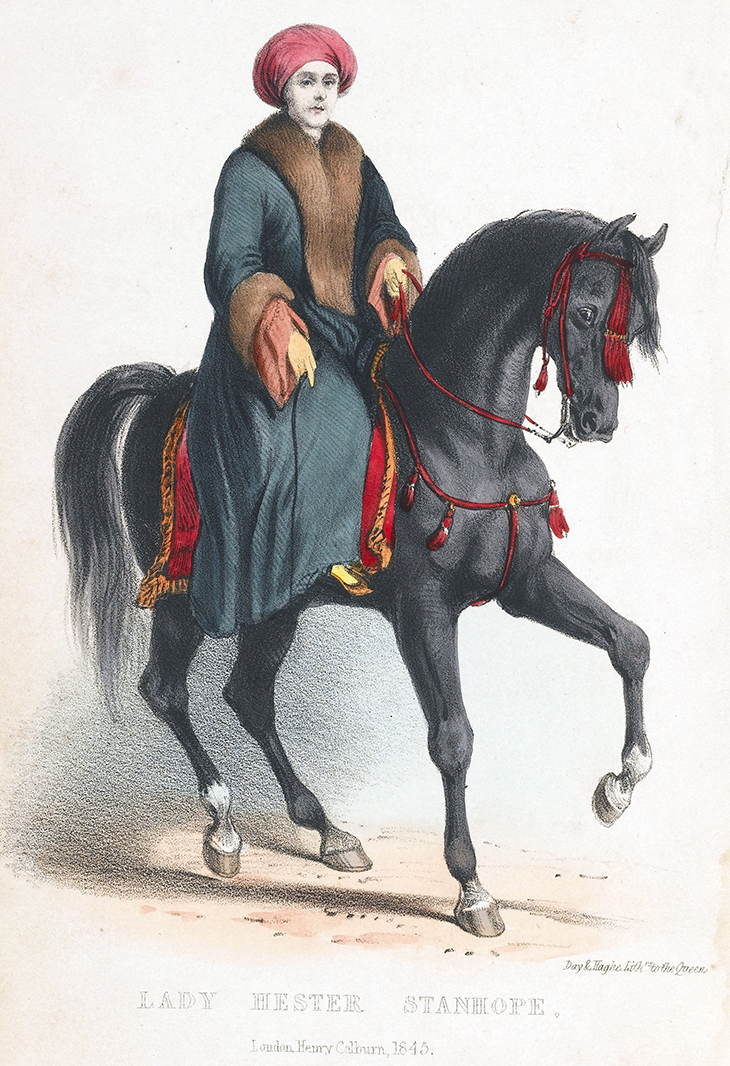

Lady Hester Stanhope

Among his many female friends and flirts, were Lady Hester Stanhope. The niece of British Prime Minister William Pitt (PM from 1783 to 1801 & 1804-1806), Hester lived with her uncle and was Pitt’s hostess and private secretary. Known for her wit and beauty, Lady Hester Stanhope was at the top of the social echelon in the early 1800s of Regency England..

(Lady Hester Stanhope 1816 Portrait: William Beechey)

(Lady Hester Stanhope 1816 Portrait: William Beechey)

“I can, even now, fancy that I see him riding up to her in the Park in a suit of plum-coloured clothes, to give her a stick of perfume of his own manufacture; a peculiar mark of favour, granted only on condition that she promised faithfully not to give a morsel to the Prince, who was dying to get some.” – A friend of the author, The Life of George Brummell, Esq., Commonly called Beau Brummell (1844), by Captain William Jesse

This unconventional British aristocrat of the Regency era was famed for her archaeological excursions to the Middle East, and other travels. Lady Hester departed England in 1810 with her brother James Hamilton Stanhope. At Rhodes she met Michael Bruce, who joined the travelers; they became lovers, living and traveling together for the next 3 years.

(Lady Hester Stanhope c. 1845)

(Lady Hester Stanhope c. 1845)

While attempting to sail from Constantinople to Cairo, a shipwreck stranded them at Rhodes. Lady Hester abandoned her very British garments and instead dressed in a fashion befitting a Turkish man, complete with robes, trousers, sword, etc. While traveling through Saudia Arabia she dressed as a Bedouin tribesman and was dubbed “Queen Hester”.

Michael Bruce left for Europe in 1813, and Lady Hester Stanhope remained in the Middle East. Her 1815 archaeological excavation at Ashkelon (north of Gaza) was the first of it’s kind in Palestine. She never returned to England, settling in what today is called Lebanon (between Beirut and Tyre). Gradually she withdrew more and more, even as her eccentricity continued to grow. Lady Hester Stanhope died in 1839 at the age of 63.

Lady Georgiana Spencer Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire

Other ladies with whom he was on very good terms include a woman who was an “incomparable” of her day – the former Lady Georgiana Spencer, the daughter of John, the first Earl Spencer. Lady Georgiana Spencer was born June 9, 1757, and was said to resemble her ancestor Sarah Jennings, the wife of John Churchill, The Duke of Marlborough.

(Georgiana Spencer, Lady Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire c. 1785-1787: Thomas Gainsborough)

(Georgiana Spencer, Lady Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire c. 1785-1787: Thomas Gainsborough)

Lady Georgiana Spencer married William, the Duke of Devonshire, on June 6, 1774, and promptly became a society leader, with hordes of admirers. The Duchess of Devonshire wrote poems and sent them to Brummell while he was in France, something many of his close friends also did. And yes, Lady Diana Spencer, Princess of Wales, was a direct descendant of Lady Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire.

The Two Georges Argue

Prince George continued to be a loyal friend and supporter of Beau Brummel in the early 1800s. He made Brummel a Major in 1803.

“Honourable Admiral Corwallis, etc.; War Office, Dec. 15, 1802. – Belvoir Castle Volunteers, George Brummell, Esq. to be Major” – The Morning Post, December 16, 1803

However, the relationship between the two Georges began to cool after the Prince of Wales was made Prince Regent in 1811. The Prince’s friendship had made it possible for Brummell to enjoy an increasingly expensive lifestyle, fueled by gambling debts and built on credit. Nevertheless, the Prince Regent and Brummell were increasingly on the outs with each other from that point on.

In July 1813 the “Dandy Club” founders – Brummell, Lord Alvanley, Pierrepoint, and Mildmay, friends decided to host a ball.

“A serious question however arose among them, whether they should or should not invite the Prince, who had previously quarreled with Brummell and Sir Henry Mildmay; but after a long, loyal, and solemn discussion on this most important subject, Brummell very properly laid aside his own feelings…When the Prince arrived he made one of his stately bows to Lord Alvanley and Mr. Pierrepoint, and shook each of them cordially by the hand; but of the other two gentlemen he took no notice whatever, nor would he even appear to know that they were present. The consequence was, that when the Regent retired, Brummell, justly incensed at the insult thus publicly and designedly put upon him, would not attend him to his carriage: this the Prince did not fail to observe, and the next day, when speaking of the circumstance, said ‘Had Brummell taken the cut I gave him good-humouredly, I would have renewed my intimacy with him.” – The Life of George Brummell, Esq., Commonly called Beau Brummell (1844), by Captain William Jesse

There’s a popular version of this story has it that after he was cut by the Prince Regent at the Watier’s party, Brummell loudly asked “Who’s your fat friend?”, thereby permanently cementing the rift between the two Georges. However, the source of this anecdote is unknown, and is missing from Captain Jesse’s biography. If true, it would surely have been mentioned in every account. An alternate version of this incident:

“When he had a tiff with the Prince of Wales, he met that personage on horseback. Brummell and a friend were also mounted, and the friend paused to speak to the Prince. Brummell also paused, but looked at the mass of royalty as if he was quite unconscious of its being present -. At last, just as the Prince was riding off, Brummell inquired, in a tone sufficiently audible to reach the Prince’s ears: ‘Pray, who is our fat friend?’ This non-chalance was irresistable and the Prince, bursting into a roar of laughter, turned his horse, and told Brummell that it was quite impossible to quarrel with him.” – Beau Brummell, Alexandria Gazette, May 15, 1840

(George, Prince of Wales 1792: James Gillray | George Brummell c. 1805: Richard Deighton)

(George, Prince of Wales 1792: James Gillray | George Brummell c. 1805: Richard Deighton)

Yet another tale has a totally different reason for the final dispute between the Prince of Wales and Brummell; in this version, Brummell asked the Prince of Wales to ring a bell (for a servant):

“The Prince made no remark, rose from the table, rang the bell, remained standing until it was answered, and when the servant stood at the door with a look of inquiry, said ‘Mr. Brummell’s carriage!” He then quitted the room, nor returned until the Beau had departed. From that hour Beau Brummell never put his foot within Carleton House.” – Beau Brummell, Alexandria Gazette, May 15, 1840

Whatever the cause, the decisive rift with the Prince Regent allowed creditors to begin calling in Beau Brummell’s debts, and by July of 1816 he left for France to avoid debtor’s prison in England.

“On the night that he left London, the Beau was seen as usual at the Opera, but he left early, and, without returning to his lodgings, stepped into a chaise which had been procured for him by a noble friend, and met his own carriage a short distance from town. Traveling all night as fast as four post-horses and liberal donations could enable him, the morning of the 17th dawned on him at Dover, and immediately on his arrival there, he hired a small vessel, put his carriage on board, and was landed in a few hours on the other side. By this time, the West End had awoke and missed him; particularly his tradesmen and his enemies, both of whom had long scores against him.” – The Life of George Brummell, Esq., Commonly called Beau Brummell (1844), by Captain William Jesse

Brummell’s household goods left behind at No. 13 Chapel Street were sold at auction after he left Britain, never to return. Many of his friends and supporters bid on items at the auction.

“Amongst the company present were Lords Besborough and Yarmouth, Lady Warburton…The competition for the knick-knacks and articles of virtu was very great; amongst them was a very handsome snuff-box, which, on being opened by the auctioneer before it was put up, was found to contain a piece of paper with the following sentence, in Brummell’s handwriting, upon it: – ‘This snuff-box was intended for the Prince Regent, if he had conducted himself with more propriety towards me.'” – The Life of George Brummell, Esq., Commonly called Beau Brummell (1844), by Captain William Jesse

Friends such as the Duke and Duchess of York, and most of the other royal Dukes of England (Gloucester, Argyle, Wellington, Rutland, Richmond, Beaufort, and Bedford), his long-standing friend Lord Alvanley, as well as Lords Sefton, Jersey, and others, would occasionally send him gifts and funds to help him subsist. Many also visited Brummell while he lived in Calais.

“The Duke of Wellington and suite dined at Dessin’s Hotel, having previously invited Mr. Brummell, now a resident at Calais, to their feast. The Dukes of Cambridge and Wellington, attended by six carriages, departed the same evening for Brussels.” – The Morning Chronicle, August 7, 1821

Aware of Brummel’s financial difficulties, King George IV appointed him a Consulship at Ostend in 1929, and again in Caen in 1930, to provide him with some income.

“The following anecdote illustrative of the kind feelings which the king still entertains towards his former associate, Brummell, will be read with interest. The appointment to a Consulship of the London Fashions, is filled by Brummell at the earnest intercession of Lord F. His Lordship, with his usual good nature, on hearing of the vacancy, represented to his illustrious master that Brummell much regretted certain errors and indiscretions of early days, which had given offence, when he was in the the enjoyment of courtly favour. The King, after some deliberation, said ‘Yes! but the situation is not more than three or four hundred a year, and he, perhaps, will not accept it.’ Lord F. replied, that such addition to Brummell’s income would be of great importance. ‘Well, then’, said His Majesty, ‘tell the Duke of Wellington, Brummell is an old friend of mine, and I wish him to have it.’ – Court Journal, The United States Gazette, January 19, 1930

In Calais, Brummell gradually accumulated a new mountain of new debits, finally ending up in debtor’s prison there in 1935. Brummell’s friends in England bailed him out later that year.

George Bryan “Beau” Brummell was 61 when he died in 1840 in Caens, in Normandy, France.. Advanced syphilis had driven him to insanity, and he died in an what was then called a mad-house.

“Beau Brummell – this once celebrated person…is now in confinement in a place set apart for those who labour under mental derangement, in Caen, in Normandy. This admired of all admirers is existing on the almost extorted benevolence of relations, and the contributions of old friends. The whole of his income is scarcely 100 pounds a year…Beau Brummell still imagines himself a fine gentleman, and assumes all the airs and importance of his by-gone popularity and good fortune. Amongst other feats he rings the bell of his solitary apartment continually. The keeper, who with great humanity humours his insanity, asks what commands? ‘Order my carriage’, says the light of other days, ‘I must go directly to Carlton House to see the Prince.” – The Preston Chronicle and Lancashire Advertiser, Oct. 26, 1939

He was survived by his siblings.

“William….[who] married, in May, 1800, Miss Daniel…and the latter [sister Jane, who married] a Captain [George, Esq. of Donnington, Bershire. in 1801] Blackshaw, who resided in a cottage near the Grove.” – Beaux & Belles of England: Beau Brummell (1844), by William Jesse

The Two Georges in Movies & on TV

Beau Brummell’s style and life story have more recently inspired characters in books and movies. Several feature films have been made about their live(s), notably:

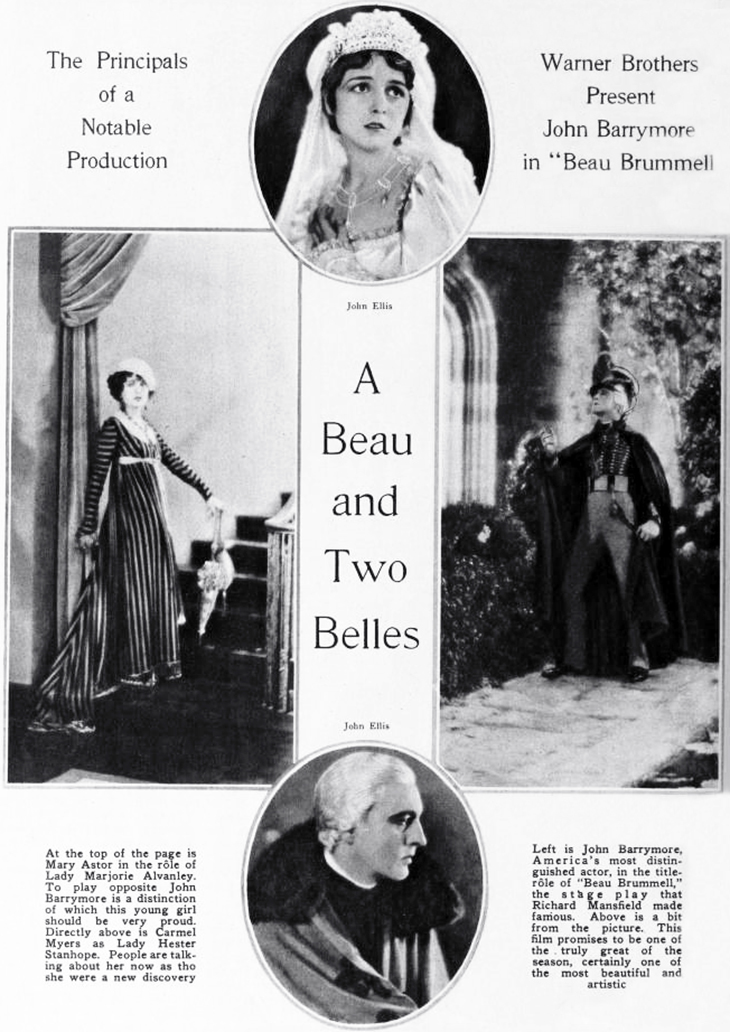

Beau Brummell (1924), a silent movie directed by Harry Beaumont, written by Dorothy Farnum and Clyde Fitch. John Barrymore stars George “Beau” Brummell. This plotline has Brummell in love with his friend Lord Alvanley’s (played by William Humphrey) fiancee / wife, Lady Margery Alvanley (Mary Astor). Willard Louis is the Prince of Wales, and Carmel Myers is Lady Hester Stanhope. Irene Rich plays Frederica, Duchess of York, and George Beranger is Lord Byron. Barrymore certainly had the ego to portray Beau Brummell to perfection. Flawed however, because it is inaccurate; for example, Lord Alvanley never married.

(Mary Astor, Carmel Myers & John Barrymore 1924 Beau Brummell)

(Mary Astor, Carmel Myers & John Barrymore 1924 Beau Brummell)

Beau Brummell (1954), starring Stewart Granger as Beau Brummell and Peter Ustinov as the Prince of Wales. Rosemary Harris is Maria Fitzherbert, the Princes’s mistress. Robert Morley plays King George III, Elizabeth Taylor is the fictional character of Lady Patricia. plays Brummell’s friend Lord Alvanley. The costumes are great – a real highlight – and one gets a sense of how the friendship between the two Georges may have been. However, the historical inaccuracies are significant, ie, Brummell maintains his svelte figure and style, dying elegantly of TB, none of which was true.

This Charming Man (2006), a made-for-TV film starring James Purefoy as Brummell, Hugh Bonneville as the Prince of Wales, Matthew Rhys as Lord Byron, and Zoe Telford as a fictional love interest Julia. The Duke and Duchess of York are played by Anthony Calf and Rebecca Johnson respectively.

Prince Regent (1979), an 8-episode TV mini-series about George, Prince of Wales. Peter Egan is the Prince, Nigel Davenport and Frances White are King George III and Queen Charlotte respectively. Bosco Hogan is Frederick, Duke of York; Susannah York plays the Prince’s mistress Maria Fitzherbert, Dinah Stabb is Princess Caroline, and Patsy Kensit and Cherie Lunghi play Princess Charlotte. Interesting that neither Lord Byron nor Beau Brummell are portrayed in the mini-series, given their impact on Regency England.

The Madness of King George (1994), an award-winning comedy-drama feature film focusing on the relationship between King George III and his oldest son George, Prince of Wales. Nigel Hawthorne is King George III, and Helen Mirren is his wife Queen Charlotte. Rupert Everett is George, Prince of Wales, and Caroline Harker is Maria Fitzherbert.

Bridgerton (2020 – ), a Netflix series based on the Regency romance book series by author Julia Quinn. Most of the characters in the TV series are fictitious, but some historical figures appear as well: Golda Rosheuvel plays Queen Charlotte, and James Fleet is King George III.